The red squares # indicate a dead subject, and the blue a living subject.

# #

#

# In[5]:

fig,axs=subplots(5,1,sharex=True,sharey=True)

fig.set_size_inches((10,6))

for i,j in enumerate(d.columns):

_=d[j].plot(ax=axs[i],marker='o')

_=axs[i].axis(ymax=1.1,ymin=-.1)

_=axs[i].set_ylabel(j)

# In[6]:

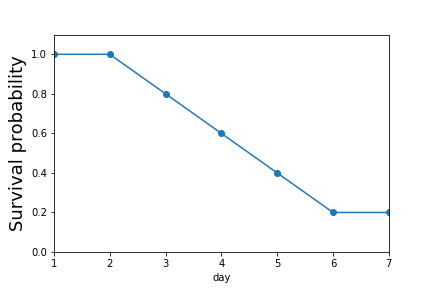

fig,ax=subplots()

_=(d.sum(axis=1)/d.shape[1]).plot(ax=ax,marker='o')

_=ax.set_ylabel('Survival probability',fontsize=18)

_=ax.axis(ymin=0,ymax=1.1)

fig.savefig('fig-statistics/survival_analysis_001.png')

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

# In[5]:

fig,axs=subplots(5,1,sharex=True,sharey=True)

fig.set_size_inches((10,6))

for i,j in enumerate(d.columns):

_=d[j].plot(ax=axs[i],marker='o')

_=axs[i].axis(ymax=1.1,ymin=-.1)

_=axs[i].set_ylabel(j)

# In[6]:

fig,ax=subplots()

_=(d.sum(axis=1)/d.shape[1]).plot(ax=ax,marker='o')

_=ax.set_ylabel('Survival probability',fontsize=18)

_=ax.axis(ymin=0,ymax=1.1)

fig.savefig('fig-statistics/survival_analysis_001.png')

#

#

#

#

# The survival probability decreases by # day.

# #

#

#

#

# There is another important recursive perspective on this

# calculation. Imagine

# there is a life raft containing $[A,B,C,D,E]$. Everyone

# survives until day two

# when \emph{A} dies. This leaves four in the life raft

# $[B,C,D,E]$. Thus, from the

# perspective of day one, the survival probability is

# the probability of surviving

# just up until day two and then surviving day two,

# $\mathbb{P}_S(t\ge 2)

# =\mathbb{P}(t\notin [0,2)\vert

# t<2)\mathbb{P}_S(t=2)=(1)(4/5)=4/5$. In words,

# this means that surviving past

# the second day is the product of surviving the

# second day itself and not having

# a death up to that point (i.e., surviving up to

# that point). Using this

# recursive approach, the survival probability for the

# third day is

# $\mathbb{P}_S(t\ge 3) =\mathbb{P}_S(t> 3)\mathbb{P}_S(t=3)=(4/5)(3/4)=3/5$.

# Recall that just before the third day, the

# life raft contains $[B,C,D,E]$ and

# on the third day we have $[B,C,E]$. Thus,

# from the perspective of just before

# the third day there are four survivors in

# the raft and on the third day there

# are three $3/4$. Using this recursive

# argument generates the same plot and comes

# in handy with censoring.

#

# ### Censoring and truncation

#

# Censoring occurs when a

# subject leaves (right censoring) or enters (left

# censoring) the study. There are

# two general types of right censoring.

# The so-called Type I right censoring is

# when a subject randomly drops

# out of the study.

# This random drop-out is another

# statistical effect that has to be accounted for

# in estimating survival. Type II

# right censoring occurs when the study is

# terminated when enough specific random

# events occur.

#

# Likewise, left censoring occurs when a subject enters the study

# prior to a certain

# date, but exactly when this happened is unknown. This happens

# in study designs

# involving two separate studies stages. For example, a subject

# might enroll in the

# first selection process but be ineligible for the second

# process. Specifically,

# suppose a study concerns drug use and certain subjects

# have used the drug before

# the study but are unable to report exactly when. These

# subjects are left

# censored. Left truncation (a.k.a. staggered entry, delayed

# entry) is similar

# except the date of entry is known. For example, a subject that

# starts taking a drug

# after being initially left out of the study.

#

# Right

# censoring is the most common so let's consider an example. Let's estimate

# the

# survival function given the following survival times in days:

#

# $$

# \{ 1, 2,3^+,4,5,6^+,7,8 \}

# $$

#

# where the censored survival times are indicated by the

# plus symbol. As before,

# the survival time at the $0^{th}$ day is $8/8=1$, the

# first day is $7/8$, the

# second day = $(7/8)(6/7)$. Now, we come to the first

# right censored entry. The

# survival time for the third day is $(7/8)(6/7)(5/5) =

# (7/8)(6/7)$. Thus, the

# subject who dropped out is not considered *dead* and

# cannot be counted as such

# but is considered just *absent* as far as the

# functional estimation of the

# probabilities goes. Continuing for the fourth day,

# we have

# $(7/8)(6/7)(5/5)(4/5)$, the fifth day, $(7/8)(6/7)(5/5)(4/5)(3/4)$, the

# sixth

# (right censored) day $(7/8)(6/7)(5/5)(4/5)(3/4)(2/2)$, and so on. We can

# summarize this in the following table:

#

# ### Hazard functions and their

# properties

#

# Generally, the *survival function* is a continuous function of time

# $S(t) =

# \mathbb{P}(T>t)$ where $T$ is the event time (e.g., time of death). Note

# that

# the cumulative density function, $F(t)=\mathbb{P}(T\le t)=1-S(t)$ and

# $f(t)=\frac{dF(t)}{dt}$ is the usual probability density function. The so-called

# *hazard function* is the instantaneous rate of failure at time $t$,

#

# $$

# h(t) = \frac{f(t)}{S(t)} = \lim_{\Delta t \rightarrow 0}\frac{\mathbb{P}(T

# \in (t,t+\Delta t]|T\ge t)}{\Delta t}

# $$

#

# Note that is a continuous-limit version of

# the calculation we performed above.

# In words, it says given the event time $T\ge

# t$ (subject has survived up to

# $t$), what is the probability of the event

# occurring in the differential

# interval $\Delta t$ for a vanishingly small

# $\Delta t$. Note that this is not

# the usual derivative-slope from calculus

# because there is no difference term in

# the numerator. The hazard function is

# also called the *force of mortality*,

# *intensity rate*, or the

# *instantaneous risk*. Informally, you can think of the

# hazard function as

# encapsulating the two issues we are most concerned about:

# deaths and the

# population at risk for those deaths. Loosely speaking, the

# probability density

# function in the numerator represents the probability of a

# death occurring in a

# small differential interval. However, we are not

# particularly interested in

# unqualified deaths, but only deaths that can happen

# to a specific at-risk

# population. Returning to our lifeboat analogy, suppose

# there are 1000 people in

# the lifeboat and the probability of anybody falling off

# the lifeboat is 1/1000.

# Two things are happening here: (1) the probability of

# the bad event is small and

# (2) there are a lot of subjects over which to spread

# the probability of that bad

# event. This means that the hazard rate for any

# particular individual is small.

# On the other hand, if there are only two

# subjects in the life raft and the

# probability of falling off is 3/4, then the

# hazard rate is high because not only

# is the unfortunate event probable, the risk

# of that unfortunate event is shared

# by only two subjects.

#

# It is a mathematical

# fact that,

#

# $$

# h(t) = \frac{-d \log S(t)}{dt}

# $$

#

# This leads to the following interpretation

#

# $$

# S(t) = \exp\left( -\int_0^t h(u)du\right) := \exp(-H(t))

# $$

#

# where $H(t)$ is the *cumulative hazard function*. Note that $H(t)=-\log S(t)$.

# Consider a subject whose survival time is 5 years. For this subject to have died

# at

# the fifth year, it had to be alive during the fourth year. Thus, the *hazard*

# at

# 5 years is the failure rate per-year, conditioned on the fact that the

# subject

# survived until the fourth year. Note that this is *not* the same as the

# unconditional failure rate per year at the fifth year, because the unconditional

# rate applies to all units at time zero and does not use information about

# survival up to that point gleaned from the other units. Thus, the *hazard

# function* can be thought of as the point-wise unconditional probability of

# experiencing the event, scaled by the fraction of survivors up to that point.

# ## Example

#

# To get a sense of this, let's consider the example where the

# probability

# density function is exponential with parameter $\lambda$,

# $f(t)=\lambda

# \exp(-t\lambda),\; \forall t>0$. This makes $S(t) = 1- F(t) =

# \exp(-t\lambda)$

# and then the hazard function becomes $h(t)=\lambda$, namely a

# constant. To see

# this, recall that the exponential distribution is the only

# continuous

# distribution that has no memory:

#

# $$

# \mathbb{P}(X\le u+t \vert X>u) = 1-\exp(-\lambda t) = \mathbb{P}(X\le t)

# $$

#

# This means no matter how long we have

# been waiting for a death to occur, the

# probability of a death from that point

# onward is the same - thus the hazard

# function is a constant.

#

#

# ### Expectations

#

# Given all these definitions, it is

# an exercise in integration by parts to show

# that the expected life remaining is

# the following:

#

# $$

# \mathbb{E}(T) = \int_0^\infty S(u) du

# $$

#

# This is equivalent to the following:

#

# $$

# \mathbb{E}(T \big\vert t=0) = \int_0^\infty S(u) du

# $$

#

# and we can likewise express the expected remaining life at $t$ as the

# following,

#

# $$

# \mathbb{E}(T \big\vert T\ge t) = \frac{\int_t^\infty S(u) du}{S(t)}

# $$

#

# ### Parametric regression models

#

# Because we are interested in how study

# parameters affect survival, we need a

# model that can accommodate regression in

# exogenous (independent) variables ($\mathbf{x}$).

#

# $$

# h(t\vert \mathbf{x})= h_o(t)\exp(\mathbf{x}^T \mathbf{\boldsymbol{\beta}})

# $$

#

# where $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ are the regression coefficients and $h_o(t)$ is the

# baseline instantaneous hazard function. Because the hazard function is always

# nonnegative, the the effects of the covariates enter through the exponential

# function. These kinds of models are called *proportional hazard rate models*.

# If

# the baseline function is a constant ($\lambda$), then this reduces to the

# *exponential regression model* given by the following:

#

# $$

# h(t\vert \mathbf{x}) = \lambda \exp(\mathbf{x}^T

# \mathbf{\boldsymbol{\beta}})

# $$

#

# ### Cox proportional hazards model

#

# The tricky part about the above proportional

# hazard rate model is the

# specification of the baseline instantaneous hazard

# function. In many cases, we

# are not so interested in the absolute hazard

# function (or its correctness), but

# rather a comparison of such hazard functions

# between two study populations. The

# Cox model emphasizes this comparison by using

# a maximum likelihood algorithm for

# a partial likelihood function. There is a lot

# to keep track of in this model, so

# let's try the mechanics first to get a feel

# for what is going on.

#

# Let $j$ denote the $j^{th}$ failure time, assuming that

# failure times are sorted

# in increasing order. The hazard function for subject

# $i$ at failure time $j$ is

# $h_i(t_j)$. Using the general proportional hazards

# model, we have

#

# $$

# h_i(t_j) = h_0(t_j)\exp(z_i \beta) := h_0(t_j)\psi_i

# $$

#

# To keep it simple, we have $z_i \in \{0,1\}$ that indicates membership in the

# experimental group ($z_{i}=1$) or the control group ($z_i=0$).

# Consider the

# first failure time, $t_1$ for subject $i$ failing is the hazard

# function

# $h_i(t_1)=h_0(t_1)\psi_{i}$. From the definitions, the probability that

# subject

# $i$ is the one who fails is the following:

#

# $$

# p_1 = \frac{h_{i}(t_1)}{\sum h_k(t_1)}= \frac{h_{0}(t_1)\psi_i}{\sum h_0(t_1)

# \psi_k}

# $$

#

# where the summation is over all surviving units up to that point. Note that the

# baseline hazard cancels out and gives the following,

#

# $$

# p_1=\frac{\psi_{i}}{\sum_k \psi_k}

# $$

#

# We can keep computing this for the other failure times to obtain

# $\{p_1,p_2,\ldots\,p_D\}$. The product of all of these is the *partial

# likelihood*, $L(\psi) = p_1\cdot p_2\cdots p_D$. The next step is to maximize

# this partial likelihood (usually logarithm of the partial likelihood) over

# $\beta$. There are a lot of numerical issues to keep track of here. Fortunately,

# the Python `lifelines`

# module can keep this all straight for us.

#

# Let's see how

# this works using the `Rossi` dataset that is available in

# lifelines.

# In[7]:

from lifelines.datasets import load_rossi

from lifelines import CoxPHFitter, KaplanMeierFitter

rossi_dataset = load_rossi()

# The Rossi dataset dataset concerns prison recidivism. The `fin` variable

# indicates whether or not the subjects received financial assistance upon

# discharge from prison.

#

# * `week`: week of first arrest after release, or

# censoring time.

#

# * `arrest`: the event indicator, equal to 1 for those arrested

# during the period of the study and 0 for those who were not arrested.

#

# * `fin`:

# a factor, with levels yes if the individual received financial aid after release

# from prison, and no if he did not; financial aid was a randomly assigned factor

# manipulated by the researchers.

#

# * `age`: in years at the time of release.

#

# *

# `race`: a factor with levels black and other.

#

# * `wexp`: a factor with levels

# yes if the individual had full-time work experience prior to incarceration and

# no if he did not.

#

# * `mar`: a factor with levels married if the individual was

# married at the time of release and not married if he was not.

#

# * `paro`: a

# factor coded yes if the individual was released on parole and no if he was not.

# * `prio`: number of prior convictions.

#

# * `educ`: education, a categorical

# variable coded numerically, with codes 2 (grade 6 or less), 3 (grades 6 through

# 9), 4 (grades 10 and 11), 5 (grade 12), or 6 (some post-secondary).

#

# * `emp1` -

# `emp52`: factors coded yes if the individual was employed in the corresponding

# week of the study and no otherwise.

# In[8]:

rossi_dataset.head()

# Now, we just have to set up the calculation in `lifelines`, using the

# `scikit-

# learn` style. The `lifelines` module handles the censoring

# issues.

# In[9]:

cph = CoxPHFitter()

cph.fit(rossi_dataset,

duration_col='week',

event_col='arrest')

cph.print_summary() # access the results using cph.summary

# The values in the summary are plotted in

# [Figure](#fig:survival_analysis_002).

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

# There is another important recursive perspective on this

# calculation. Imagine

# there is a life raft containing $[A,B,C,D,E]$. Everyone

# survives until day two

# when \emph{A} dies. This leaves four in the life raft

# $[B,C,D,E]$. Thus, from the

# perspective of day one, the survival probability is

# the probability of surviving

# just up until day two and then surviving day two,

# $\mathbb{P}_S(t\ge 2)

# =\mathbb{P}(t\notin [0,2)\vert

# t<2)\mathbb{P}_S(t=2)=(1)(4/5)=4/5$. In words,

# this means that surviving past

# the second day is the product of surviving the

# second day itself and not having

# a death up to that point (i.e., surviving up to

# that point). Using this

# recursive approach, the survival probability for the

# third day is

# $\mathbb{P}_S(t\ge 3) =\mathbb{P}_S(t> 3)\mathbb{P}_S(t=3)=(4/5)(3/4)=3/5$.

# Recall that just before the third day, the

# life raft contains $[B,C,D,E]$ and

# on the third day we have $[B,C,E]$. Thus,

# from the perspective of just before

# the third day there are four survivors in

# the raft and on the third day there

# are three $3/4$. Using this recursive

# argument generates the same plot and comes

# in handy with censoring.

#

# ### Censoring and truncation

#

# Censoring occurs when a

# subject leaves (right censoring) or enters (left

# censoring) the study. There are

# two general types of right censoring.

# The so-called Type I right censoring is

# when a subject randomly drops

# out of the study.

# This random drop-out is another

# statistical effect that has to be accounted for

# in estimating survival. Type II

# right censoring occurs when the study is

# terminated when enough specific random

# events occur.

#

# Likewise, left censoring occurs when a subject enters the study

# prior to a certain

# date, but exactly when this happened is unknown. This happens

# in study designs

# involving two separate studies stages. For example, a subject

# might enroll in the

# first selection process but be ineligible for the second

# process. Specifically,

# suppose a study concerns drug use and certain subjects

# have used the drug before

# the study but are unable to report exactly when. These

# subjects are left

# censored. Left truncation (a.k.a. staggered entry, delayed

# entry) is similar

# except the date of entry is known. For example, a subject that

# starts taking a drug

# after being initially left out of the study.

#

# Right

# censoring is the most common so let's consider an example. Let's estimate

# the

# survival function given the following survival times in days:

#

# $$

# \{ 1, 2,3^+,4,5,6^+,7,8 \}

# $$

#

# where the censored survival times are indicated by the

# plus symbol. As before,

# the survival time at the $0^{th}$ day is $8/8=1$, the

# first day is $7/8$, the

# second day = $(7/8)(6/7)$. Now, we come to the first

# right censored entry. The

# survival time for the third day is $(7/8)(6/7)(5/5) =

# (7/8)(6/7)$. Thus, the

# subject who dropped out is not considered *dead* and

# cannot be counted as such

# but is considered just *absent* as far as the

# functional estimation of the

# probabilities goes. Continuing for the fourth day,

# we have

# $(7/8)(6/7)(5/5)(4/5)$, the fifth day, $(7/8)(6/7)(5/5)(4/5)(3/4)$, the

# sixth

# (right censored) day $(7/8)(6/7)(5/5)(4/5)(3/4)(2/2)$, and so on. We can

# summarize this in the following table:

#

# ### Hazard functions and their

# properties

#

# Generally, the *survival function* is a continuous function of time

# $S(t) =

# \mathbb{P}(T>t)$ where $T$ is the event time (e.g., time of death). Note

# that

# the cumulative density function, $F(t)=\mathbb{P}(T\le t)=1-S(t)$ and

# $f(t)=\frac{dF(t)}{dt}$ is the usual probability density function. The so-called

# *hazard function* is the instantaneous rate of failure at time $t$,

#

# $$

# h(t) = \frac{f(t)}{S(t)} = \lim_{\Delta t \rightarrow 0}\frac{\mathbb{P}(T

# \in (t,t+\Delta t]|T\ge t)}{\Delta t}

# $$

#

# Note that is a continuous-limit version of

# the calculation we performed above.

# In words, it says given the event time $T\ge

# t$ (subject has survived up to

# $t$), what is the probability of the event

# occurring in the differential

# interval $\Delta t$ for a vanishingly small

# $\Delta t$. Note that this is not

# the usual derivative-slope from calculus

# because there is no difference term in

# the numerator. The hazard function is

# also called the *force of mortality*,

# *intensity rate*, or the

# *instantaneous risk*. Informally, you can think of the

# hazard function as

# encapsulating the two issues we are most concerned about:

# deaths and the

# population at risk for those deaths. Loosely speaking, the

# probability density

# function in the numerator represents the probability of a

# death occurring in a

# small differential interval. However, we are not

# particularly interested in

# unqualified deaths, but only deaths that can happen

# to a specific at-risk

# population. Returning to our lifeboat analogy, suppose

# there are 1000 people in

# the lifeboat and the probability of anybody falling off

# the lifeboat is 1/1000.

# Two things are happening here: (1) the probability of

# the bad event is small and

# (2) there are a lot of subjects over which to spread

# the probability of that bad

# event. This means that the hazard rate for any

# particular individual is small.

# On the other hand, if there are only two

# subjects in the life raft and the

# probability of falling off is 3/4, then the

# hazard rate is high because not only

# is the unfortunate event probable, the risk

# of that unfortunate event is shared

# by only two subjects.

#

# It is a mathematical

# fact that,

#

# $$

# h(t) = \frac{-d \log S(t)}{dt}

# $$

#

# This leads to the following interpretation

#

# $$

# S(t) = \exp\left( -\int_0^t h(u)du\right) := \exp(-H(t))

# $$

#

# where $H(t)$ is the *cumulative hazard function*. Note that $H(t)=-\log S(t)$.

# Consider a subject whose survival time is 5 years. For this subject to have died

# at

# the fifth year, it had to be alive during the fourth year. Thus, the *hazard*

# at

# 5 years is the failure rate per-year, conditioned on the fact that the

# subject

# survived until the fourth year. Note that this is *not* the same as the

# unconditional failure rate per year at the fifth year, because the unconditional

# rate applies to all units at time zero and does not use information about

# survival up to that point gleaned from the other units. Thus, the *hazard

# function* can be thought of as the point-wise unconditional probability of

# experiencing the event, scaled by the fraction of survivors up to that point.

# ## Example

#

# To get a sense of this, let's consider the example where the

# probability

# density function is exponential with parameter $\lambda$,

# $f(t)=\lambda

# \exp(-t\lambda),\; \forall t>0$. This makes $S(t) = 1- F(t) =

# \exp(-t\lambda)$

# and then the hazard function becomes $h(t)=\lambda$, namely a

# constant. To see

# this, recall that the exponential distribution is the only

# continuous

# distribution that has no memory:

#

# $$

# \mathbb{P}(X\le u+t \vert X>u) = 1-\exp(-\lambda t) = \mathbb{P}(X\le t)

# $$

#

# This means no matter how long we have

# been waiting for a death to occur, the

# probability of a death from that point

# onward is the same - thus the hazard

# function is a constant.

#

#

# ### Expectations

#

# Given all these definitions, it is

# an exercise in integration by parts to show

# that the expected life remaining is

# the following:

#

# $$

# \mathbb{E}(T) = \int_0^\infty S(u) du

# $$

#

# This is equivalent to the following:

#

# $$

# \mathbb{E}(T \big\vert t=0) = \int_0^\infty S(u) du

# $$

#

# and we can likewise express the expected remaining life at $t$ as the

# following,

#

# $$

# \mathbb{E}(T \big\vert T\ge t) = \frac{\int_t^\infty S(u) du}{S(t)}

# $$

#

# ### Parametric regression models

#

# Because we are interested in how study

# parameters affect survival, we need a

# model that can accommodate regression in

# exogenous (independent) variables ($\mathbf{x}$).

#

# $$

# h(t\vert \mathbf{x})= h_o(t)\exp(\mathbf{x}^T \mathbf{\boldsymbol{\beta}})

# $$

#

# where $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ are the regression coefficients and $h_o(t)$ is the

# baseline instantaneous hazard function. Because the hazard function is always

# nonnegative, the the effects of the covariates enter through the exponential

# function. These kinds of models are called *proportional hazard rate models*.

# If

# the baseline function is a constant ($\lambda$), then this reduces to the

# *exponential regression model* given by the following:

#

# $$

# h(t\vert \mathbf{x}) = \lambda \exp(\mathbf{x}^T

# \mathbf{\boldsymbol{\beta}})

# $$

#

# ### Cox proportional hazards model

#

# The tricky part about the above proportional

# hazard rate model is the

# specification of the baseline instantaneous hazard

# function. In many cases, we

# are not so interested in the absolute hazard

# function (or its correctness), but

# rather a comparison of such hazard functions

# between two study populations. The

# Cox model emphasizes this comparison by using

# a maximum likelihood algorithm for

# a partial likelihood function. There is a lot

# to keep track of in this model, so

# let's try the mechanics first to get a feel

# for what is going on.

#

# Let $j$ denote the $j^{th}$ failure time, assuming that

# failure times are sorted

# in increasing order. The hazard function for subject

# $i$ at failure time $j$ is

# $h_i(t_j)$. Using the general proportional hazards

# model, we have

#

# $$

# h_i(t_j) = h_0(t_j)\exp(z_i \beta) := h_0(t_j)\psi_i

# $$

#

# To keep it simple, we have $z_i \in \{0,1\}$ that indicates membership in the

# experimental group ($z_{i}=1$) or the control group ($z_i=0$).

# Consider the

# first failure time, $t_1$ for subject $i$ failing is the hazard

# function

# $h_i(t_1)=h_0(t_1)\psi_{i}$. From the definitions, the probability that

# subject

# $i$ is the one who fails is the following:

#

# $$

# p_1 = \frac{h_{i}(t_1)}{\sum h_k(t_1)}= \frac{h_{0}(t_1)\psi_i}{\sum h_0(t_1)

# \psi_k}

# $$

#

# where the summation is over all surviving units up to that point. Note that the

# baseline hazard cancels out and gives the following,

#

# $$

# p_1=\frac{\psi_{i}}{\sum_k \psi_k}

# $$

#

# We can keep computing this for the other failure times to obtain

# $\{p_1,p_2,\ldots\,p_D\}$. The product of all of these is the *partial

# likelihood*, $L(\psi) = p_1\cdot p_2\cdots p_D$. The next step is to maximize

# this partial likelihood (usually logarithm of the partial likelihood) over

# $\beta$. There are a lot of numerical issues to keep track of here. Fortunately,

# the Python `lifelines`

# module can keep this all straight for us.

#

# Let's see how

# this works using the `Rossi` dataset that is available in

# lifelines.

# In[7]:

from lifelines.datasets import load_rossi

from lifelines import CoxPHFitter, KaplanMeierFitter

rossi_dataset = load_rossi()

# The Rossi dataset dataset concerns prison recidivism. The `fin` variable

# indicates whether or not the subjects received financial assistance upon

# discharge from prison.

#

# * `week`: week of first arrest after release, or

# censoring time.

#

# * `arrest`: the event indicator, equal to 1 for those arrested

# during the period of the study and 0 for those who were not arrested.

#

# * `fin`:

# a factor, with levels yes if the individual received financial aid after release

# from prison, and no if he did not; financial aid was a randomly assigned factor

# manipulated by the researchers.

#

# * `age`: in years at the time of release.

#

# *

# `race`: a factor with levels black and other.

#

# * `wexp`: a factor with levels

# yes if the individual had full-time work experience prior to incarceration and

# no if he did not.

#

# * `mar`: a factor with levels married if the individual was

# married at the time of release and not married if he was not.

#

# * `paro`: a

# factor coded yes if the individual was released on parole and no if he was not.

# * `prio`: number of prior convictions.

#

# * `educ`: education, a categorical

# variable coded numerically, with codes 2 (grade 6 or less), 3 (grades 6 through

# 9), 4 (grades 10 and 11), 5 (grade 12), or 6 (some post-secondary).

#

# * `emp1` -

# `emp52`: factors coded yes if the individual was employed in the corresponding

# week of the study and no otherwise.

# In[8]:

rossi_dataset.head()

# Now, we just have to set up the calculation in `lifelines`, using the

# `scikit-

# learn` style. The `lifelines` module handles the censoring

# issues.

# In[9]:

cph = CoxPHFitter()

cph.fit(rossi_dataset,

duration_col='week',

event_col='arrest')

cph.print_summary() # access the results using cph.summary

# The values in the summary are plotted in

# [Figure](#fig:survival_analysis_002).

#

#

#

#

# This shows the fitted coefficients # from the summary table for each covariate.

# #

#

# In[10]:

ax=cph.plot();

ax.figure.savefig('fig-statistics/survival_analysis_002.png')

# The Cox proportional hazards model object from `lifelines` allows us to predict

# the survival function for an individual with given covariates, assuming that

# the

# individual just entered the study. For example, for the first individual

# (i.e.,

# row) in the `rossi_dataset`, we can use the model to predict the

# survival

# function for that individual.

# In[11]:

cph.predict_survival_function(rossi_dataset.iloc[0,:]).head()

# This result is plotted in [Figure](#fig:survival_analysis_003).

# In[12]:

fig,ax =subplots()

_=cph.predict_survival_function(rossi_dataset.iloc[0,:]).plot(ax=ax)

_=ax.set_ylabel('Survival probability',fontsize=16)

_=ax.set_title('Survival probability for $0^{th}$ subject',fontsize=18)

fig.savefig('fig-statistics/survival_analysis_003.png')

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

# In[10]:

ax=cph.plot();

ax.figure.savefig('fig-statistics/survival_analysis_002.png')

# The Cox proportional hazards model object from `lifelines` allows us to predict

# the survival function for an individual with given covariates, assuming that

# the

# individual just entered the study. For example, for the first individual

# (i.e.,

# row) in the `rossi_dataset`, we can use the model to predict the

# survival

# function for that individual.

# In[11]:

cph.predict_survival_function(rossi_dataset.iloc[0,:]).head()

# This result is plotted in [Figure](#fig:survival_analysis_003).

# In[12]:

fig,ax =subplots()

_=cph.predict_survival_function(rossi_dataset.iloc[0,:]).plot(ax=ax)

_=ax.set_ylabel('Survival probability',fontsize=16)

_=ax.set_title('Survival probability for $0^{th}$ subject',fontsize=18)

fig.savefig('fig-statistics/survival_analysis_003.png')

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

# The Cox # proportional hazards model can predict the survival probability for an # individual based on their covariates.

# #

#

# In[ ]:

#

#

# In[ ]: